Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare, often aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. It comprises 18% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and 1% to 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1 The incidence of AITL in the United States is estimated to be 0.05 cases per 100,000 person-years,2 and there is a slight male predominance.1,3,4 It typically presents in the seventh decade of life; however, cases have been reported in adults ranging from 20 to 91 years of age.3

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma presents with lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and systemic B symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, generalized pruritus).4-6 There are cutaneous manifestations in up to 50% of cases4,5,7 and frequently signs of autoimmune disorder.4,5 The diagnosis often is made by excisional lymph node biopsy. Lymph node specimens characteristically have a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that includes numerous B cells often infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and a relatively small population of atypical T lymphocytes.8 Identification of this neoplastic population of CD4+CD8− T lymphocytes expressing normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, chemokine CXCL13, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) confirms the diagnosis of AITL.9,10 These malignant cells can be identified in skin specimens in cases of cutaneous metastatic disease.11,12 We present a case originally misdiagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that was later identified as AITL on skin biopsy.

Case Report

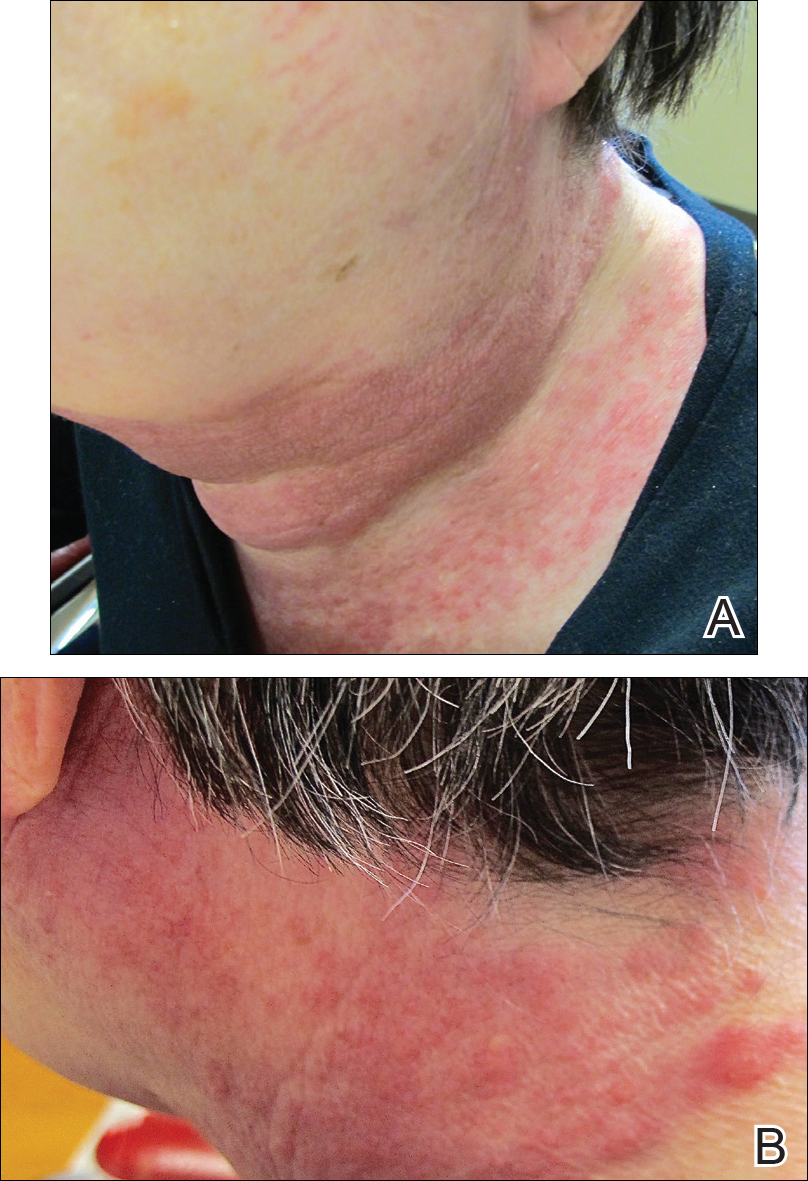

A 72-year-old woman presented with a pruritic erythematous eruption around the neck of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed 3 months prior based on results from a right cervical lymph node biopsy. She was treated with bendamustine and rituximab. On physical examination there were erythematous edematous papules coalescing into indurated plaques around the neck. The differential diagnosis included drug hypersensitivity reaction, herpes zoster, urticaria, and cutaneous metastasis. Two punch biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin and tissue culture.

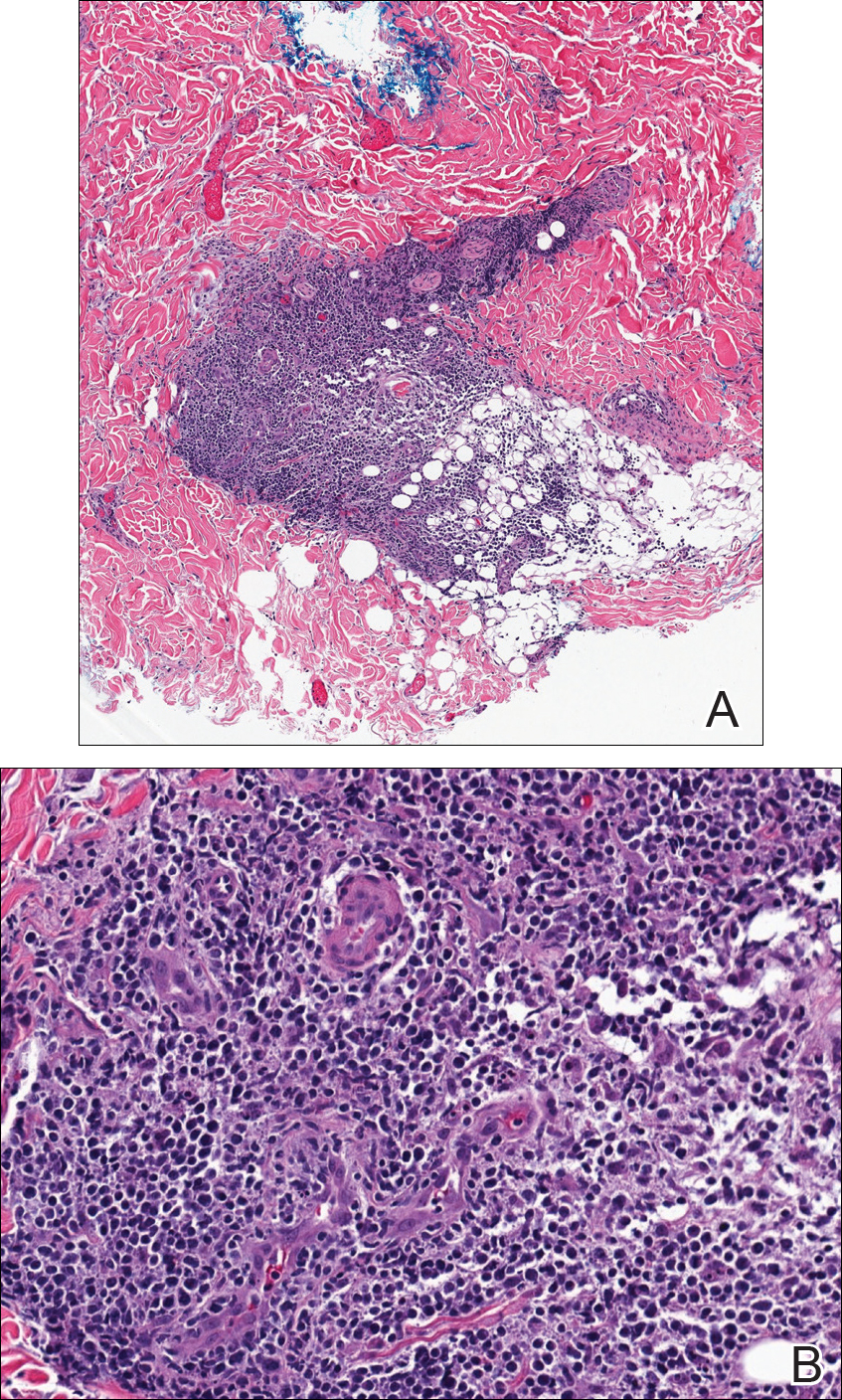

Tissue cultures and viral polymerase chain reaction were negative. Histopathologic examination revealed a scant atypical lymphoid infiltrate focally involving the deep dermis. The cells were medium to large in size and contained hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei (Figure 2). They were positive for CD3 and CD4, which was concerning for T-cell lymphoma. The histologic report of the excisional lymph node biopsy done 3 months prior described an atypical lymphoid neoplasm with extensive necrosis and extranodal spread that stained positively for CD20 (Figure 3).

Further staining of this cervical lymph node specimen revealed large atypical lymphoid cells positive for CD3, CD10, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), BCL-6, and PD-1. There were intermixed mature B lymphocytes positive for CD20 and BCL-2. Chromogenic in situ hybridization with probes for EBV showed numerous positive cells throughout the infiltrate. Polymerase chain reaction demonstrated a T-cell population with clonally rearranged T-cell receptor genes. Primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains showed no evidence of a clonal B-cell population.

Additional staining of the atypical cutaneous lymphocytes revealed positivity for CD3, CD10, and PD-1. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings of both specimens supported the diagnosis of AITL.

The patient declined further treatment and chose hospice care.