On an EEG, epileptiform activity is seen as spikes or sharp waves and indicates potential for epileptic seizures.

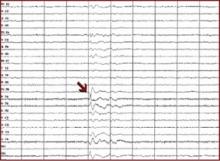

- Focal epileptiform activity is consistent with seizures of focal origin (e.g., simple partial, complex partial, or partial onset seizure with secondary generalization into tonic-clonic seizure).

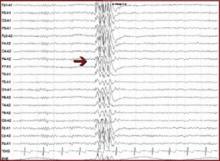

- Generalized epileptiform activity is consistent with seizures of generalized onset (e.g., absence, myoclonic, or primary generalized tonic-clonic seizure).

Interictal spikes (between seizures) are consistent with, but not diagnostic of, seizures and epilepsy. An ictal discharge (rhythmic, persistent epileptiform activity) on an EEG accompanied by a clinical change in behavior is diagnostic of a seizure.

Focal epileptiform activity

Generalized epileptiform activity

Based on early studies, EEG results can show epileptiform activity in some normal brains.1 On the other hand, only about 50% of patients with epilepsy will show epileptiform activity on a single EEG. Thus, some EEG abnormalities in psychiatric patients may not be related to either epilepsy or the psychiatric disorder, and a normal EEG does not exclude the possibility of epileptic seizures.

Question the patient for a history of other factors that may predispose him or her to seizures, such as:

- family history of seizures

- previous traumatic brain injury

- structural brain abnormality.

In light of this EEG, brain MRI is indicated. In this case the patient could be counseled to avoid seizure triggers (e.g., sleep deprivation). Because a long list of medications can lower the seizure threshold, the clinician must weigh the risks and benefits of using any medication in patients with increased susceptibility for seizures.

Case 2: Seizures or panic attacks?

Mr. B, age 31, is referred by his primary care physician for “spells” that began several years ago and recently increased in frequency to three to four times per week. The episodes start with a feeling of fear, “butterflies” in his stomach, and hyperventilation. These feelings intensify within minutes; each episode lasts 10 to 30 minutes.

The patient is usually aware of his surroundings during the episodes but twice has lost consciousness for less than 1 minute. There is no evidence of incontinence or tongue biting. Four years ago, the patient was involved in a motor vehicle accident and lost consciousness for about 30 minutes.

An EEG shows intermittent slowing from the left temporal region, and brain MRI is normal. Treatment with a benzodiazepine shortens the attacks. Where do you proceed from here?

Mr. B presents a diagnostic dilemma. Characteristics of his episodes may be seen in panic attacks, temporal lobe complex partial seizures, and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, which is the preferred term for pseudoseizures (Table).2

One option would be to see how he responds to an agent that would treat seizures but not panic attacks (e.g., carbamazepine) or one that would treat panic attacks but not seizures (e.g., a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor). Because his episodes are frequent, however, a more appropriate option would be to admit him for video/EEG monitoring, which can distinguish among these possible diagnoses with almost 100% accuracy.

Case 3: Attention disorder or epilepsy?

Miss C, age 9, is referred for possible ADHD. Her teachers notice she has difficulty following lessons in class but is intelligent and usually motivated. Her grades have been dropping. Her family reports she has episodes during which she stares and is unable to answer questions for 3 to 5 seconds, but she exhibits no other seizure-like manifestations. A trial of methylphenidate has not improved the symptoms. What should you try next?

This patient presents with symptoms that could be consistent with absence seizures. EEG would be diagnostic if it showed generalized spike and wave. Absence seizures (sometimes called petit mal) usually present in childhood and are characterized by recurrent brief staring spells with no postictal confusion or other clinical manifestations.

Patients with childhood absence epilepsy are usually of normal intelligence and only rarely have other associated seizure types (e.g., myoclonus or tonic-clonic). Seizures of approximately 3 to 5 seconds may occur up to 100 times a day and thus may be mistaken for attention problems.

EEG shows characteristic generalized three-per-second spike and wave, which is often precipitated by hyperventilation or photic stimulation. Ethosuximide or valproate can completely control seizures in most cases.

Case 4: Emergency use of EEG

Ms. D, age 21, is brought to the emergency department by her mother with symptoms of confusion. Ms. D has a long history of temporal lobe complex partial seizures, and her mother thinks she may have missed some doses of her antiepileptic drugs (carbamazepine and valproate). Yesterday Ms. D had two complex partial seizures but returned to baseline. Today she had three complex partial seizures within 2 hours and has not returned to baseline.