Effects of the sociopolitical climate

In the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged during a time of deep sociopolitical divide. Accordingly, beliefs about viral infectivity, severity of illness, and precautionary measures have varied. Some politicians, media outlets, and physicians have shared information that contradicts guidelines and recommendations from mainstream national and international medical and scientific organizations. Patients who subscribe to these reports and beliefs may not meet the threshold for understanding, appreciation, or reasoning. For example, if a patient’s beliefs about the virus depart from well-established medical evidence, they would technically lack understanding. The usual remedy for addressing misunderstanding is education and time. However, because of the divisiveness of the sociopolitical climate, the limited time physicians have with patients, and the fact that many DMC assessments will occur in acute-care settings, it may be difficult or near impossible to correct the misunderstanding.

The sociopolitical climate and its accompanying potentially erroneous or imbalanced narrative may thus directly impact patients’ understanding, appreciation, and reasoning. However, it can be problematic to declare incapacity in a patient whose understanding, appreciation, and reasoning arise from widely shared and relatively fixed sociopolitical values. Additionally, some clinicians and ethicists might object to declaring incapacity in a patient with no underlying mental or neurologic dysfunction. The United States has a functional approach to capacity, based solely on meeting criteria for the 4 functional abilities.3,13 Mental or neurologic dysfunction is not legally required in the United States, but in practice, the consideration of incapacity is often closely linked to some form of cognitive impairment.14 Other countries do make dysfunction a specific criterion; for example, the United Kingdom dictates that mental incapacity can only occur in someone with “impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.”15

Leaving against medical advice

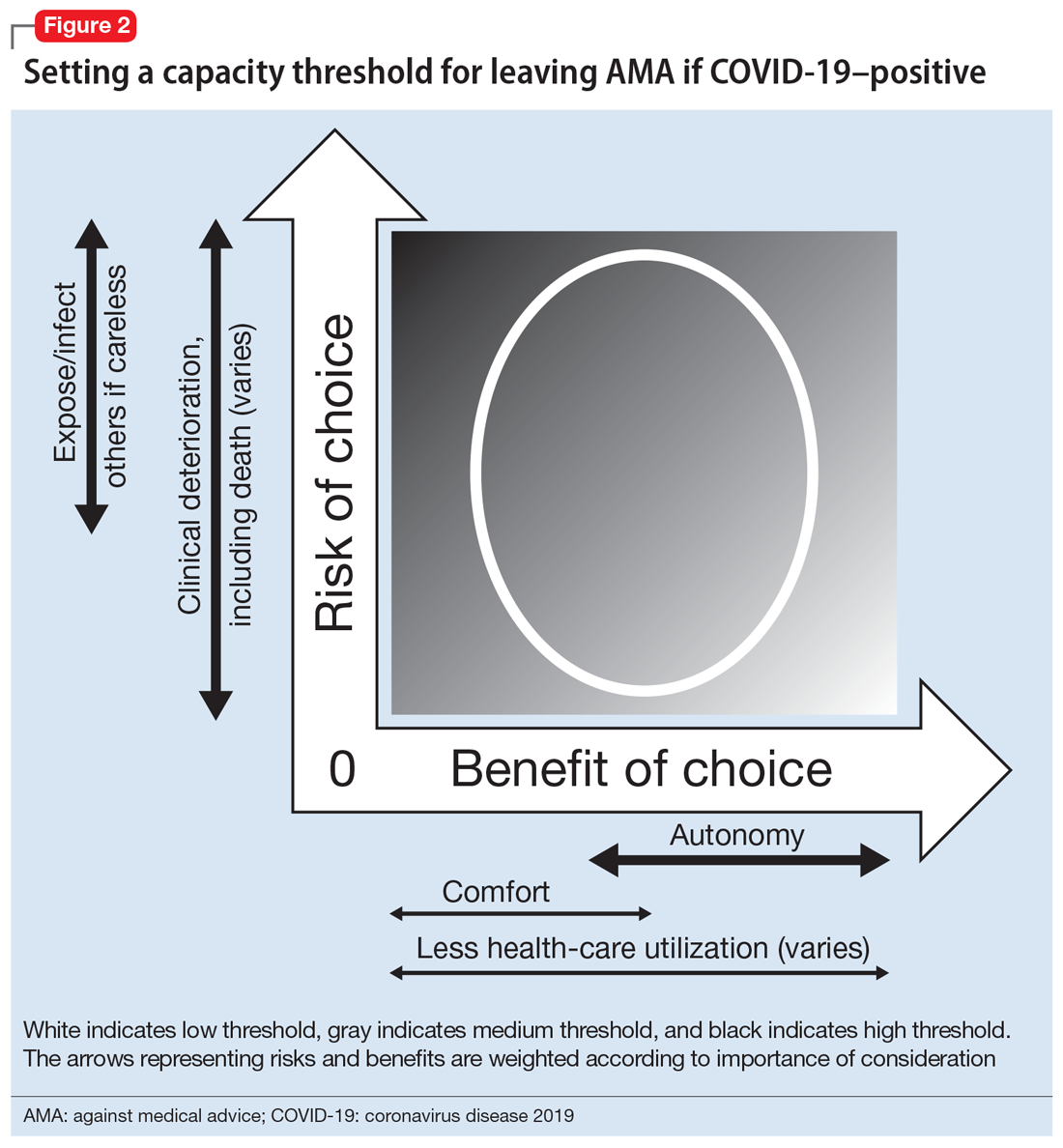

In the case of a patient who is COVID-19–positive, symptomatic, and wants to leave AMA, the threshold is automatically elevated because of societal-level risks (the risk of potential exposure or infection of others if a patient who is COVID-19–positive is not properly isolated). Furthermore, the individual risk of the patient leaving AMA depends on his/her age, comorbidities, and current clinical status; because of the uncertainty and rapid deterioration seen with COVID-19 illness, the calculated risk may actually be higher than for a non-COVID-19–related illness. Thus, in order to leave AMA, the patient’s responses must be fairly robust (Figure 2). Table 1 describes the information needed for robust understanding, appreciation, and reasoning.

For patients who do not meet this threshold, it is important to determine why. If a patient has a psychiatric condition that not only impacts DMC but also meets criteria for a psychiatric hold (ie, an imminent risk of harm to self or others), a psychiatric hold should be placed. If the patient does not meet the threshold because of altered mental status or some other neurologic or cognitive comorbidity, a medical hold should be placed. Most states do not have an explicit legal basis for a medical hold, although it does fall under the incapacity laws in the United States; in the absence of a surrogate, declaration of medical emergency can also be used if applicable.16,17 As a caveat, it can be difficult to detain someone on a medical hold because security officers may be afraid to physically detain someone without explicit legal paperwork.17

If a patient does not meet the capacity threshold but there does not seem to be a psychiatric, neurologic, or cognitive explanation, several options are possible. The first step would be to assess whether the patient is amenable to further discussion and compromise. A nonjudgmental and nonconfrontational approach that aims to further clarify the patient’s perspective and identify shared goals is key. Any plan that lowers the risks sufficiently would allow the patient to leave by lowering the capacity threshold. Enlisting the support of family and friends can be helpful. If this does not work, theoretically the patient should be detained in the hospital. Practically speaking, this may be difficult or unadvised. First, as described above, security officers may refuse to physically detain the patient.17 Second, the patient’s legally mandated surrogate may espouse similar COVID-related views as the patient; thus, this approach may not help keep the patient in the hospital. If the physician has serious concern about the risk of the patient leaving, he/she would have to consult the facility’s Ethics and Legal staff to determine capacity of the surrogate. Third, it can be problematic to declare incapacity in a patient whose understanding, appreciation, and reasoning arise from widely shared and relatively fixed sociopolitical values. In the current sociopolitical climate, involuntary detention may elicit a political backlash. Using medical detention for impending deterioration of clinical status would be more acceptable than using medical detention for isolation. Presently, there are no such laws for patients with COVID-19 (although this is not without precedent, as with active tuberculosis or Ebola18,19), but individual jurisdictions may have isolation or quarantine orders; the local health department could be contacted and may evaluate on a case-by-case basis.

Continue to: Refusing to seek medical care