Mrs. C, age 75, is transferred to our inpatient medical/surgical hospital from a psychiatric hospital after presenting with shortness of breath and altered mental status.

Eight days earlier, Mrs. C had been admitted to the psychiatric hospital for bipolar mania with psychotic features. While there, Mrs. C received quetiapine, 400 mg nightly, and an initial valproic acid (VPA) dosage of 500 mg 2 times daily. While receiving VPA 500 mg 2 times daily, her VPA total level was 62 µg/mL, which is on the lower end of the therapeutic range (50 to 125 µg/mL). This prompted the team at the psychiatric hospital to increase her VPA dosage to 500 mg 3 times daily the day before she was transferred to our hospital.

At our hospital, she is found to be in hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia. Upon admission, her laboratory data show evidence of infection and anemia and she also has an albumin level of 3.0 g/dL (normal range: 3.5 to 5.5 g/dL). All other laboratory values, including liver enzymes, are unremarkable. She is started on IV levofloxacin. Her previous medications—quetiapine and VPA—are continued at their same dosages and frequencies from her inpatient psychiatric stay.

From hospital Day 3 to Day 6, Mrs. C experiences gradual improvement in her respiratory and mental status. However, on hospital Day 7, she has extreme somnolence and altered mental status without respiratory involvement. Our team suspects VPA toxicity and/or VPA-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy (VHE).

VPA-induced hyperammonemia

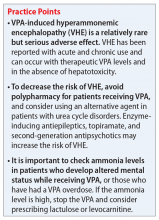

Hyperammonemia can occur in individuals receiving VPA and is most often asymptomatic. However, elevations in ammonia may lead to VHE, which is a rare but serious adverse effect. VHE has been reported early in treatment, in acute VPA overdose, and in chronic VPA use despite normal doses and levels.1 It also can occur in the absence of clinical and laboratory evidence of hepatotoxicity. VHE is associated with significant morbidity and CNS damage. Symptoms of VHE include vomiting, lethargy, and confusion. If left untreated, VHE can lead to coma and death.

Mechanism of VHE. The exact mechanism of VHE is unknown.1-3 Ammonia is a toxic base produced by deamination of amino acids. The liver eliminates ammonia via the urea cycle.2 Valproic acid metabolites, propionate and 4-en-VPA, can directly inhibit N-acetyl glutamate, which can disrupt the urea cycle, leading to elevated ammonia levels.3 Long-term or high-dose VPA can lead to carnitine deficiency, primarily by inhibiting its biosynthesis and depleting stores.4 Carnitine deficiency leads to disturbances in mitochondrial function, causing inhibition of the urea cycle and increasing ammonia. CNS toxicity due to hyperammonemia is thought to be due to activation of glutamate receptors.3

Risk factors. Co-administration of other antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) with VPA is a risk factor for VHE.1,5 This happens because enzyme-inducing AEDs such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine can increase toxic metabolites of VPA, which can lead to hyperammonemia. Topiramate can also inhibit the urea cycle, leading to increased ammonia levels. Additionally, co-administration of VPA with quetiapine, paliperidone, risperidone, or aripiprazole has been reported to increase the risk of VHE.1,5 Intellectual disability, carnitine deficiency, low albumin, and abnormal liver function have also been reported to increase the risk of VHE.1,5

Continue to: Diagnosis and management