EVALUATION Significant impairment

CT head and MRI brain scans without contrast suggest mild generalized atrophy that is more prominent in frontal and parietal areas, but the scans are otherwise unremarkable overall. A PET scan is significant for hypoactivity in the temporal and parietal lobes but, again, the images are interpreted as unremarkable overall.

Ms. P scores 21 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicative of significant cognitive impairment (normal score, ≥26). This is a 3-point decline on a MoCA performed during her admission 5 years earlier.

Ms. P scores 8 on the Middlesex Elderly Assessment of Mental State, the lowest score in the borderline range of cognitive function for geriatric patients. She scores 13 on the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, indicating that she needs maximal supervision, structure, and support to live in the community. Particularly notable is that Ms. P failed 5 out of 6 subtests in money management—a marked decline for someone who had worked as a senior accountant.

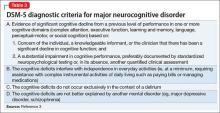

Given Ms. P’s significant cognitive decline from premorbid functioning, verified by collateral information, and current cognitive deficits established on standardized tests, we determine that, in addition to a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, she might meet DSM-5 criteria for unspecified major neurocognitive disorder if her functioning does not improve with treatment.

The authors’ observations

There is scant literature on late-onset schizoaffective disorder. Webster and Grossberg13 conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,730 patients age >65 who were admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit from 1988 to 1995. Of these patients, 166 (approximately 10%) were found to have late life-onset psychosis. The psychosis was attributed to various causes, such as dementia, depression, bipolar disorder, medical causes, delirium, medication toxicity. Two patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 2 were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (the authors did not provide additional information about the patients with schizoaffective disorder). Brenner et al14 reports a case of late-onset schizoaffective disorder in a 70-year-old female patient. Evans et al15 compared outpatients age 45 to 77 with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (n = 29), schizophrenia (n = 154), or nonpsychotic mood disorder (n = 27) and concluded that late-onset schizoaffective disorder might represent a variant of LOS in clinical symptom profiles and cognitive impairment but with additional mood symptoms.16

How would you begin treating Ms. P?

a) start a mood stabilizer

b) start an atypical antipsychotic

c) obtain more history and collateral information

d) recommend outpatient treatment

The authors’ observations

Given Ms. P’s manic symptoms, thought disorder, and history of psychotic symptoms with diagnosis of LOS, we assigned her a presumptive diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. From the patient report, collateral information from her mother, earlier documented collateral from her husband, and chart review, it was apparent to us that Ms. P’s psychiatric history went back only 10 years—therefore meeting temporal criteria for LOS.

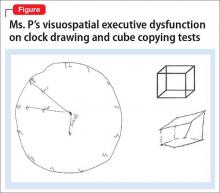

Clinical assessment (Figure) and standardized tests revealed the presence of neurocognitive deficits sufficient to meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder (Table 33). The pattern of neurocognitive deficits is consistent with an AD-like amnestic picture, although no clear-cut diagnosis was present, and the neurocognitive disorder was better classified as unspecified rather than of a particular type. It remains uncertain whether cognitive deficits of severity that meet criteria for major neurocognitive disorder are sufficiently accounted for by the diagnosis of LOS alone. Unless diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are expanded to include cognitive deficits, a separate diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder is warranted at present.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy

On the unit, Ms. P is observed by nursing staff wandering, with some pressured speech but no behavioral agitation. Her clothing had been bizarre, with multiple layers, and, at one point, she walks with her gown open and without undergarments. She also reports to the nurses that she has a lot of sexual thoughts. When the interview team enters her room, they find her masturbating.

Ms. P is started on aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, titrated to 20 mg/d, and divalproex sodium, 500 mg/d. The decision to initiate a cognitive enhancer, such as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, is deferred to outpatient care to allow for the possibility that her cognitive features will improve after the psychosis is treated.

By the end of first week, Ms. P’s manic features are no longer prominent but her thought process continues to be bizarre, with poor insight and judgment. She demonstrates severe ambivalence in all matters, consistently gives inconsistent accounts of the past, and makes dramatic false statements.

For example, when asked about her children, Ms. P tells us that she has 6 children—the youngest 3 months old, at home by himself and “probably dead by now.” In reality, she has only a 20-year-old son who is studying abroad. Talking about her marriage, Ms. P says she and her husband are not divorced on paper but that, because they haven’t had sex for 8 years, the law has provided them with an automatic divorce.