Few ObGyn clinicians have faced a patient with a cesarean-scar pregnancy (CSP). Those few were confronted with a management dilemma. Continue the gestation, which would expose the mother to an elevated risk of heavy bleeding? Or terminate the pregnancy? And if termination is the patient’s choice, what is the most effective method?

The literature contains more than 750 reports of CSP, ranging from a single sporadic case to a series of one to two dozen cases. It is impossible to make sense of the numerous treatments used in the past, which were “tested” on extremely small numbers of patients (sometimes as few as one). In this article, we formulate a management plan for the diagnosis and treatment of CSP based on an in-depth review of the published literature and our personal experience in treating more than four dozen patients with CSP.

We’re all familiar with the “epidemic” of cesarean deliveries in this country, including late consequences of cesarean such as placenta previa and morbidly adherent placenta. One of the long-term consequences of cesarean delivery—the first-trimester CSP—is less well known and documented.

Our in-depth review of 751 CSP cases found no less than 30 published therapeutic approaches.1 No consensus exists as to management guidelines. We have formulated this clinical guide, based on the literature and our experience managing CSP, for clinicians who encounter this dangerous form of pregnancy.2

DIAGNOSIS REQUIRES TRANSVAGINAL SONOGRAPHY

Transvaginal sonography (TVS) is thought to be the best and first-line diagnostic tool, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reserved for cases in which there is a diagnostic problem.

In making a diagnosis, consider two main differential diagnoses:

- Cervical pregnancy—This type of gestation is more likely to occur in women with no history of cesarean delivery

- Spontaneous miscarriage in progress—In a number of cases, the miscarriage happened to be caught on imaging as it passed the area where the CSP usually resides. Because there is no live embryo or fetus in spontaneous miscarriage, a heartbeat cannot be documented.

Components of diagnosis by TVS

Accurate identification of CSP depends on the following sonographic criteria:

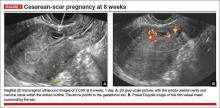

- empty uterine cavity and cervical canal (FIGURE 1A)

- close proximity of the gestational sac and the placenta to the anterior uterine surface within the scar or niche of the previous cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1B, 2A, and 2B)

- color flow signals between the posterior bladder wall and the gestation within the placenta (FIGURES 1B, 2B, and 3B)

- abundant blood flow around the gestational sac, at times morphing into an arteriovenous malformation with a high peak systolic velocity blood flow demonstrable on pulsed Doppler.

Our analysis of 751 cases of CSP found that almost a third—30%—were misdiagnosed, contributing to a large number of treatment complications. Most of these complications could have been avoided if diagnosis had been early and correct. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome seemed to be. This was true even when treatment modalities with slightly higher complication rates were used in very early gestation.

Related articles:

• Is the hCG discriminatory zone a reliable indicator of intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; February 2012)

• Can a single progesterone test distinguish viable and nonviable pregnancies accurately in women with pain or bleeding? Linda R. Chambliss, MD, MPH (Examining the Evidence; March 2013)

THOROUGH COUNSELING OF THE PATIENT IS PARAMOUNT

Once a diagnosis of CSP has been established, the patient should be counseled about her options. The presence of a live CSP requires immediate and decisive action to prevent further growth of the embryo or fetus. Literature from the past decade, particularly from the past several years, makes evidence-based counseling possible.

In general, treatment should be individualized, based on the patient’s age, number of previous cesarean deliveries, number of children, and the expertise of the clinicians managing her care. Options include:

- termination of the pregnancy

- continuation of the pregnancy with the possibility of delivering a live offspring, provided the patient understands that a morbidly adherent placenta may occur, often necessitating emergency hysterectomy.3,4

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Most treatment regimens and combinations thereof can be classified as one of the following:

- Surgical—requiring general anesthesia and either laparotomy with excision or hysterectomy, or laparoscopic or hysteroscopic excision followed by dilation and curettage (D&C).

- Minimally invasive—involving local injection of methotrexate or potassium chloride or systemic intervention, involving a major procedure such as uterine artery embolization in combination with a less complicated one: intramuscular injection of methotrexate in a single or a multidose regimen.

A variety of simultaneous as well as sequential combination treatments also were used. More recently, an ingenious adjunct to treatment is gaining attention: insertion and inflation of a Foley balloon catheter to prevent or tamponade bleeding.