The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- Strategies that may help you avoid MVI

- Tips on how to recognize it

- What to do when MVI occurs

CASE Trocar insertion, then a bleed

Sophia, a 29-year-old nulliparous patient, undergoes diagnostic laparoscopy after unsuccessful medical therapy for chronic pelvic pain. After insufflation, a reusable 11-mm trocar with obturator is placed. A survey of the pelvis and abdomen reveals a 10-cm retroperitoneal hematoma in the midline just below the umbilicus.

What is the best way to manage this hemorrhage?

Contrary to widespread belief, gynecologic laparoscopy has a rate of major complication similar to, not higher than, that of laparotomy—but it has a higher rate of major vascular injury (MVI), defined as laceration of the aorta, inferior vena cava, or common iliac or external iliac vessels.1 In fact, MVI appears to be somewhat exclusive to laparoscopy.

In a large review of 29,966 gynecologic laparoscopies, investigators found the surgeon’s level of experience to be an important variable in the overall complication rate but not in the incidence of MVI.2 This means patients are at risk of MVI regardless of how many or how few laparoscopic procedures you perform.

What can a surgeon do to avert this type of injury? The most important strategy is to be conversant with variables that clearly increase the risk, as well as behaviors and protocols that can minimize it. This article offers five pearls—from prevention to postop management.

1. Pay attention to subtlety, starting at the preop visit

When a marriage counselor was asked which significant actions can improve a relationship, he responded: “The little things are the big things.”

To minimize the risk of vascular injury, a meticulous surgeon begins with the “little things” at the preoperative evaluation. Important considerations include the patient’s height, weight, and body mass index (BMI). Does she have a history of abdominal surgery or pelvic disease that could suggest intra-abdominal adhesions and anatomic distortion?

It is important to discuss the risk of bowel or vascular injury, as well as the need to convert to an open procedure, with all patients, but particularly with those who are thin or who have abnormal abdominal findings.

A recent randomized clinical trial found that routine mechanical bowel preparation did not facilitate surgery or decrease the incidence of complications, but may be helpful in select cases.3

2. Don’t undervalue that ounce of prevention

A commuter commented to her friend that she thought the bus driver had exceptional driving skill. The friend couldn’t understand this remark. “The driver hasn’t been challenged yet,” the friend argued. “She hasn’t needed to demonstrate any action in the face of an emergency—so how do you know what level of skill she has?”

“That is precisely the point,” the commuter replied. “The driver has exercised extreme judgment and caution so as not to require using her superior skill in an emergency.”

It is always better to avoid a potentially catastrophic complication than to manage it. The first requirement is vigilance in preparing for laparoscopy. It is important to ensure that the patient is in the supine position during initial entry and that her arms are comfortably tucked on both sides. In 85% of cases, the aorta can be palpated.4

Select an entry technique wisely

Base this decision on experience, patient characteristics, the surgical procedure, and availability of equipment. No entry technique or device can be considered completely safe.

Most vascular injuries occur during the initial phase of laparoscopy:

- As many as 39% are related to placement of the Veress needle

- As many as 37.9% are related to placement of the primary trocar.5

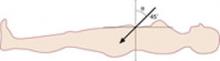

The classic “closed” method of laparoscopy has been used successfully for decades. In thin patients, insert the Veress needle toward the uterus. In computed tomography studies, an angle of at least 34 degrees has been shown to avoid the aorta and its bifurcation (FIGURE 1).6

The right common iliac vessel is most commonly involved in injury, given its anatomic relationship overriding the inferior vena cava (FIGURE 2). When you stand at the patient’s left, the Veress needle can inadvertently be directed off to the right of midline, in harm’s way of the right common iliac vessels.

FIGURE 1 In thin women, insert the Veress needle toward the uterus