For more than 45 years, gynecologists have used hysteroscopy to diagnose endometrial carcinoma and to associate morphologic descriptive terms with visual findings.1 Today, considerably more clinical evidence supports visual pattern recognition to assess the risk for and presence of endometrial carcinoma, improving observer-dependent biopsy of the most suspect lesions (VIDEO 1).

In this article, I discuss the clinical evolution of hysteroscopic pattern recognition of endometrial disease and review the visual findings that correlate with the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma. In addition, I have provided 9 short videos that show hysteroscopic views of various endometrial pathologies in the online version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

The negative hysteroscopic view defined

In 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer confirmed the diagnostic superiority of visually directed biopsy. He demonstrated the advantages of using hysteroscopy and directed biopsy in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to obtain a more accurate diagnosis compared with dilation and curettage (D&C) alone (sensitivity, 98% vs 65%, respectively).2

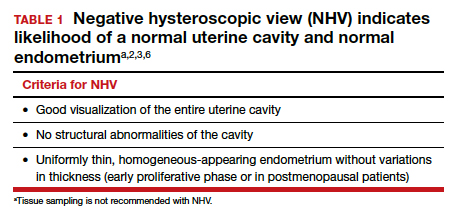

Also derived from this work is the clinical application of the “negative hysteroscopic view” (NHV). Loffer used the following criteria to define the NHV: good visualization of the entire uterine cavity, no structural abnormalities of the cavity, and a uniformly thin, homogeneous-appearing endometrium without variations in thickness (TABLE 1). The last criterion can be expected to occur only in the early proliferative phase or in postmenopausal women.

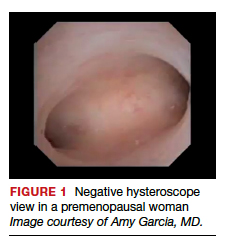

Use of hysteroscopy therefore can predict accurately the absence of intrauterine and endometrial pathology when visual findings are negative and tissue sampling is not warranted (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 2).

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Efforts in hysteroscopic classification of endometrial carcinoma

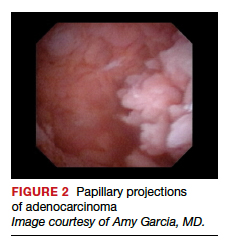

Lesion morphologic characteristics. Sugimoto was among the first to describe the hysteroscopic identification of visual morphologic features that are most likely to be associated with endometrial carcinoma.1 Patients with AUB were evaluated with hysteroscopy as first-line management to describe lesion morphology and confirm biopsy with histopathology. Sugimoto classified endometrial carcinoma as circumscribed or exophytic with distinct forms, such as polypoid, nodular, papillary, and ulcerated (FIGURE 2). Diffuse or endophytic carcinoma is defined by an ulcerated type of lesion that indicates necrosis; this is most likely to represent an undifferentiated tumor. Sugimoto also described abnormal vascularity that often is associated with carcinoma.1

Endometrial features. Valli and Zupi created a nomenclature and classification for hysteroscopic endometrial lesions by prospectively grading 4 features: thickness, surface, vascularization, and color.3 Features were scored based on the degree of abnormality and could be considered to be of low or high risk for the presence of carcinoma. High-risk hysteroscopic features included endometrial thickness greater than 10 mm, polymorphous surface, irregular vascularization, and white-grayish color. The sensitivity for accurately diagnosing endometrial lesions was 86.9% for mild lesions and 96% for severe lesions.3 Also, these investigators confirmed the clinical value of the NHV and associated overall risk of precancer or cancer of the endometrium.

Continue to: Amount of endometrial involvement...