The past year was an exciting one in obstetrics. The landmark ARRIVE trial presented at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s (SMFM) annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine contradicted a long-held belief about the safety of elective labor induction. In a large randomized trial, Cahill and colleagues took a controversial but practical clinical question about second-stage labor management and answered it for the practicing obstetrician in the trenches. Finally, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) placed new emphasis on the oft overlooked but increasingly more complicated postpartum period, offering guidance to support improving care for women in this transitional period.

Ultimately, this was the year of the patient, as research, clinical guidelines, and education focused on how to achieve the best in safety and quality of care for delivery planning, the delivery itself, and the so-called fourth trimester.

ARRIVE: Labor induction at 39 weeks reduces CD rate with no difference in perinatal death or serious outcomes

Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

The term "elective induction of labor" has long had a negative connotation because of its association with increased CD rates and adverse perinatal outcomes. This view was based on results from older observational studies that compared outcomes for labor induction with those of spontaneous labor. In more recent observational studies that more appropriately compared labor induction with expectant management, however, elective induction of labor appears to be associated with similar CD rates and perinatal outcomes.

To test the hypothesis that elective induction would have a lower risk for perinatal death or severe neonatal complications than expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women, Grobman and colleagues conducted A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management (ARRIVE).1

Study population, timing of delivery, and trial outcomes

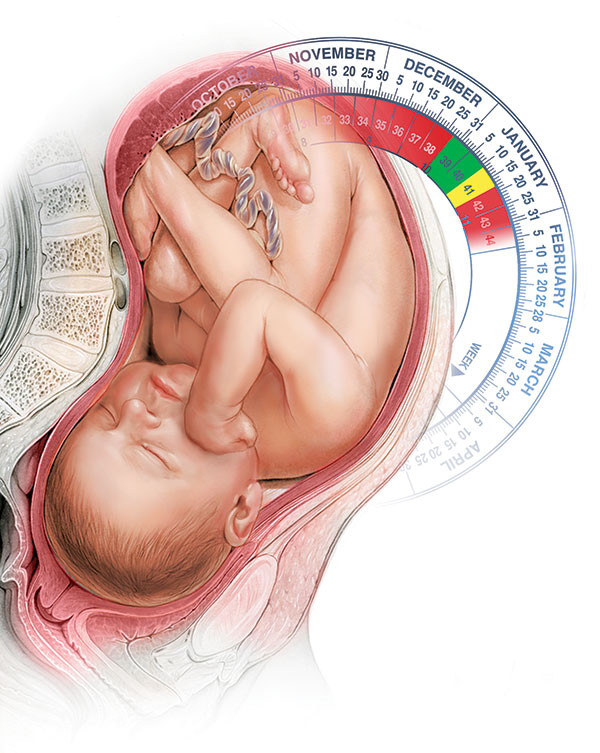

This randomized controlled trial included 6,106 women at 41 US centers in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Study participants were low-risk nulliparous women with a singleton vertex fetus who were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 39 to 39 4/7 weeks (n = 3,062) or expectant management (n = 3,044) until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks.

"Low risk" was defined as having no maternal or fetal indication for delivery prior to 40 5/7 weeks. Reliable gestational dating was required.

While no specific protocol for induction of labor management was required, there were 2 requests: 1) Cervical ripening was requested for an unfavorable cervix (63% of participants had a modified Bishop score <5), and 2) a duration of at least 12 hours after cervical ripening, rupture of membranes, and use of uterine stimulant was requested before performing a CD for "failed induction" (if medically appropriate).

The primary outcome was a composite of perinatal death or serious neonatal complications. The main secondary outcome was CD.

Potentially game-changing findings

The investigators found that there was no statistically significant difference between the elective induction and expectant management groups for the primary composite perinatal outcome (4.3% vs 5.4%; P = .049, with P<.046 prespecified for significance). In addition, the rate of CD was significantly lower in the labor induction group than in the expectant management group (18.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001).

Other significant findings in secondary outcomes included the following:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were significantly lower in the labor induction group compared with the expectant management group (9.1% vs 14.1%; P<.001).

- The labor induction group had a longer length of stay in the labor and delivery unit but a shorter postpartum hospital stay.

- The labor induction group reported less pain and more control during labor.

Results refute negative notion of elective labor induction

The authors concluded that in a low-risk nulliparous patient population, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks does not increase the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes and decreases the rate of CD and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Additionally, they noted that induction at 39 weeks should not be avoided with the goal of preventing CD, as even women with an unfavorable cervix had a lower rate of CD in the induction group compared with the expectant management group.

After publication of the ARRIVE trial findings, both ACOG and SMFM released statements supporting elective labor induction at or beyond 39 weeks’ gestation in low-risk nulliparous women with good gestational dating.2,3 They cited the following as important issues: adherence to the trial inclusion criteria except for research purposes, shared decision-making with the patient, consideration of the logistics and impact on the health care facility, and the yet unknown impact on cost. Finally, it should be a priority to avoid the primary CD for a failed induction by allowing a longer latent phase of labor, as long as maternal and fetal conditions allow. In my practice, I actively offer induction of labor to most of my patients at 39 weeks after a discussion of the risks and benefits.

Continue to: Immediate pushing in second stage...