Finally, we spoke with primary care providers, physicians who were viewed as leaders in their clinics. They described trepidation among their teams about adopting an innovation that would lead to patients being identified as at risk for suicide. Their concern was not that integrating depression care was not the right thing to do in the primary care setting; indeed, they had a strong and genuine desire to provide better depression care for their patients. Their concern was that the primary care clinic was not equipped to manage a suicidal patient safely and effectively. This concern was real, and it was pervasive. After all, the typical primary care office visit was already replete with problem lists too long to be managed effectively in the diminishing amount of time allotted to each visit. Screening for depression would only make matters worse [12]. Furthermore, identifying a patient at risk for suicide was not uncommon in our primary care setting. Between 2006 and 2012, an average of 16% of primary care patients screened each year had reported some degree of suicidal ideation (as measures by a positive response on question 9 of the PHQ-9). These discussions showed us that the model of depression care we were trying to spread into primary care was not designed with an explicit and confident approach to suicide—it was not Perfect Depression Care.

Leveraging Suicide As a Driver of Spread

When we realized that the anxiety surrounding the management of a suicidal patient was the biggest obstacle to Perfect Depression Care spread to primary care, we decided to turn this obstacle into an opportunity. First, an interdisciplinary team developed a practice guideline for managing the suicidal patient in general medical settings. The guideline was based on the World Health Organization’s evidence-based guidelines for addressing mental health disorders in nonspecialized health settings [13] and modified into a single page to make it easy to adopt. Following the guideline was not at all a requirement, but doing so made it very easy to identify patients at potential risk for suicide and to refer them safely and seamlessly to the next most appropriate level of care.

Second, and most importantly, BHS made a formal commitment to provide immediate access for any patient referred by a primary care provider following the practice guideline. BHS pledged to perform the evaluation on the same day as the referral was made and without any questions asked. Delivering on this promise required BHS to develop and implement reliable processes for its ambulatory centers to receive same-day referrals from any one of 27 primary care clinics. Success meant delighting our customers in primary care while obviating the expense and trauma associated with sending patients to local emergency departments. This work was hard. And it was made possible by the culture within BHS of pursuing perfection.

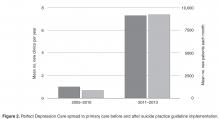

The practice guideline was adopted readily and rapidly, and its implementation was followed by much success. During the 5 years of Perfect Depression Care spread when there was no practice guideline for managing the suicidal patient in general medical settings, we achieved a spread rate of 1 clinic per year. From 2010 to 2012, after the practice guideline was implemented, the model was spread to 22 primary care clinics, a rate of 7.3 clinics per year. This operational improvement brought with it powerful clinical improvement as well. After the implementation of the practice guideline, the average number of primary care patients receiving Perfect Depression Care increased from 835 per month to 9186 per month ( Figure 2