Investigators documented the route (IV or oral) and antihypertensive(s) medication selected for each patient. Adverse effects and any changes to patients’ outpatient medication regimens were noted. Investigators also assessed days to next medical contact after ED discharge to determine whether follow-up occurred according to the recommended standard of 7 days.9 Days to next medical contact was defined as any contact—in person or by telephone—that was documented in the electronic health record after the index ED visit.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, and standard deviation, were used to analyze data.

Results

A total of 1,052 patients presented with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg and for whom antihypertensive medication was ordered but not necessarily given in the ED. Of the total, 724 patients were excluded because of hospital admission for other primary diagnoses; however, 6 of these patients were admitted for hypertensive urgency. The final analysis included 132 patients who presented with the primary condition of elevated BP without any accompanying symptoms. Among these patients, 2 had repeat ED visits for AH during the specified time frame.

Each ED visit was treated as a separate occurrence.Most patients were male with an average age of 63 years and documented history of hypertension. Nearly all patients had established primary care within the NFSGVHS. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus (36%), followed by coronary artery disease (27%) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (21%) (Table 1). About one-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition, and slightly more than half were referred to the ED by primary care or specialty clinics.

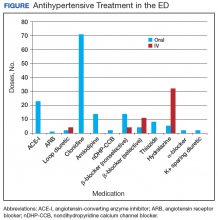

The average BP and heart rate at ED presentation was 199/112 mm Hg and 76 beats per minute, respectively.In the ED, 130 patients received BP treatment (Table 2). Medication was ordered for 2 patients who did not receive treatment. In total, 12 different medication classes were used for treating patients with AH in the ED (Figure).

Most were treated with at least 1 oral antihypertensive; clonidine was the most common (48% of orally administered doses). In this study, 13% of patients received IV-only intervention; most were treated with hydralazine. Among the patients in the study, 22% were treated with a combination of oral and IV antihypertensives. No immediate AEs were noted for medications administered in the ED; however, 1 patient returned to the ED with angioedema after initiating an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor at an ED visit 5 days earlier.Treatment in the ED resulted in an average BP and heart rate reduction of 27/20 mm Hg and 5 beats per minute, respectively. About 80% of patients had a basic metabolic panel drawn, and there were no instances of acute kidney injury. Of the patients in the study 38% had cardiac enzymes collected, and only 1 patient had a positive result, which was determined to be unrelated to acute coronary syndrome. Forty-one (31%) of patients had a urinalysis; 12 has positive results for hematuria, and 18 revealed proteinuria. Of note, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. The reason these patients were admitted is unclear.

At discharge, ED providers made changes to 54% of patients’ outpatient antihypertensive regimens. These changes included adding a new medication (68%), increasing the dosage of an existing medication (24%), or multiple changes (8%). Refills were provided for 18% of prescriptions. Follow-up within 7 days from ED discharge was recorded for 34% of patients. One patient received follow-up outside the NFSGVHS and was not included in this analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the incidence of AH in a VA ED and describe how these patients were managed. Overall, the rate of patients presenting to the ED with AH during the study period was about 1 patient every 8 days or 45 patients per year. By comparison, more than 30,000 patients are seen at the NFSGVHS ED annually. Although AH seems to be an uncommon occurrence, study findings raise questions about the value of managing the condition in the ED.

This study found several management strategies as well as noteworthy trends. For example, laboratory tests were not ordered routinely for all patients, suggesting that some ED providers question their use for AH. There were no patients with acute elevations in serum creatinine that indicated acute kidney injury, and although hematuria and proteinuria were common findings, neither were specific for acute injury. However, there were findings typical of chronic hypertension, and urinalysis may provide little benefit when testing for acute kidney injury. Only 1 patient showed elevated cardiac enzymes, which was determined to be a result of CKD.

Although not included in the final analysis, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency were similar in that they had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. Collectively, these findings support existing literature that questions the utility of laboratory testing of patients with AH in the ED.10

Patients also were treated with a variety of antihypertensive agents in the ED. One explanation might be outpatient nonadherence with medications. In patients with AH, it is common to provide doses of chronic medications that the patient might have missed and should be taking on a regular basis. Therefore, assessing adherence with current medications before modifying chronic therapy is an important initial step when managing AH.

Although oral agents primarily were used, IV antihypertensives were administered to about one-third of patients. Preference for IV administration in the ED might be related to its ability to lower BP quickly. The practice of obtaining IV access for medication in a patient with AH is costly, unnecessary, and potentially harmful.7 The authors theorize that this practice is performed, in many cases, as an attempt to expedite ED discharge after an acceptable BP reading is documented.

Rapid reductions in BP can precipitate hypoperfusion inadvertently and are more likely to occur with IV agents than with oral ones. Therefore, the safety, convenience, and cost savings associated with oral administration make it the preferred route for managing AH.

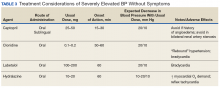

Oral antihypertensives with desired therapeutic and pharmacokinetic properties are listed in Table 3. When used appropriately, these agents are well tolerated and effective and could be given in an ambulatory care clinic without the need for intensive monitoring.