Providing comprehensive, integrated, behavioral intervention services to address the prevalent condition of chronic, noncancer pain is a growing concern. Although the biopsychosocial model (BPS) and stepped-care approaches have been understood and discussed for some time, clinician and patient understanding and investment in these approaches continue to face challenges. Moreover, even when resources (eg, staffing, referral options, space) are available, clinicians and patients must engage in meaningful communication to achieve this type of care.

Importantly, engagement means moving beyond diagnosis and assessment and offering interventions that provide psychoeducation related to the chronic pain cycle. These interventions address maladaptive cognitions and beliefs about movement and pain; promote paced, daily physical activity and engagement in life; and help increase coping skills to improve low mood or distress, all fundamental components of the BPS understanding of chronic pain.

Background

Chronic, noncancer pain is a prevalent presentation in primary care settings in the U.S. and even more so for veterans.1 Fifty percent of male veterans and 75% of female veterans report chronic pain as an important condition that impacts their health.2 An important aspect of this prevalence is the focus on opioid pain medication and medical procedures, both of which draw more narrowly on the biomedical model. Additional information on the longer term use of pain procedures and opioid medications is now available,and given some risks and limitations (eg, tolerance, decreasing efficacy, opioid-induced medical complications), the need to study and offer other options is gaining attention.3 Behavioral chronic pain management has a clear historic role that draws on the BPS modeland Gate Control Theory.3-6

More recently, the National Strategy of Chronic Pain collaborative and stepped-care models extended this literature, outlining collaboration and levels of care depending on the chronicity of the pain experience as well as co-occurring conditions and patient presentations.7,8 The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), the gold standard in interdisciplinary pain management programs, calls for further resources and coordination of these efforts, including a tertiary level of care representing the highest step in the stepped-care model.8

These interdisciplinary, integrative pain management programs, which include functional restoration and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, have been effective for the treatment of chronic pain.9-12However, the staffing, resources, clinical access, and coordination of this complex care may not be feasible in many health care settings. For example, a 2005 survey reported that there were only 200 multidisciplinary pain programs in the U.S., and only 84 of them were CARF accredited.13 By 2011 the number of CARF-accredited programs had decreased to 64 (the number of nonaccredited programs was not reported for 2011).13

Furthermore, engagement in behavioral pain management services is a challenge: Studies show that psychosocial interventions are underused, and a majority of studies may not report quantitatively or qualitatively on patient adherence or engagement in these services.14 These realities introduce the idea that coordinated appointments between 2 or 3 different disciplines available in primary care may be a feasible step toward implementing more comprehensive, optimal care models.

Behavioral pain management interventions that uphold the BPS also call on the idea of active self-management. Therefore, effective communication is fundamental at both the provider-patient and interprofessional levels to enhance engagement in health care, receptiveness to interventions, and to self-management of chronic pain.11,15 How clinicians conceptualize, hold assumptions about, and communicate with patients about chronic pain management has received more attention.15,16

Clinician Considerations for Pain Management

On theclinicians’ side, monitoring assumptions about patients and awareness of their beliefs as well as the care itself are foundational in patient interactions, impacting the success of patient engagement. Awareness of the language used in these interactions and how clinicians collaborate with other professionals become salient. Coupled with the reality of high attrition, this discussion lends itself in important ways to the motivational interviewing (MI) approach that aims to meet patients “where they are” by use of open-ended questions and reflective listening to guide the conversation in the direction of contemplating or actual behavior change.17 For example, “What do you think are the best ways to manage your pain?” and “It sounds like sometimes the medicine helps, but you also want more options to feel in control of your pain.”

Given the historic focus on the biomedical approach to chronic pain, including the use of opioid medications and medical procedures as well as traditional challenges to engagement in CBT, researchers have explored whether alternative methods may increase participation and improve outcomes for behavioral self-management.3 Drawing on a history of assessing readiness for change in pain management, Kerns and colleagues offered tailored cognitive strategies or behavioral skills training depending on patient preferences.18,19 These researchers also incorporated motivational enhancement strategies in the tailored interventions and compared engagement with standard CBT for chronic pain protocol. Although they did not find significant differences in engagement between the 2 groups, participation and treatment adherence were associated with posttreatment improvements in both groups.19 Taking a step back from enhancing intervention engagement, first assessing readiness to self-manage becomes another salient exploration and step in the process.

Another element of engagement in services is referral to other clinicians. Dorflinger and colleagues made this point in a conceptual paper that broadly outlined interdisciplinary, integrative, and more comprehensive models of care for chronic pain.15 We know from integrated models that referral-based care may decrease the likelihood of participation in health care services. That is, if a patient needs to make a separate appointment and meet with a new clinician, they are more likely to decline, cancel, or not show, particularly if they are not “ready” for change. Co-located or embedded care and conjoint sessions that include a warm handoff or another clinician who joins the first appointment may reduce stigma and other relevant barriers for introducing a patient to new ideas.20

Using a conjoint session that involves a clinical pharmacy pain specialist and a health psychologist is one way in which veterans can be exposed to more chronic pain-related BPS concepts and behavioral health services than they might be exposed to otherwise. The purpose of this project was to bring awareness to a practical and clinically relevant integrated approach to the dissemination of BPS information for chronic pain management.

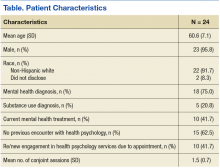

In providing this information through effective communication at the patient-provider and interprofessional levels, the clinicians’ intention was to increase patient engagement and use of BPS strategies in the self-management of chronic pain. This project also aimed to enhance engagement and improve the quality of services before acquiring additional positions and funding for a specialized pain management team. These sessions were offered at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan. Quantitative and qualitative information was examined from the conjoint and subsequent sessions that occurred in this setting.