Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, information on nonresponder characteristics was not available. Respondents covered a range of ages, with 64% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years. Respondents were men (88%) and white (49%) or African American (40%). Fifty-five percent screened positive for at least 1 mental health condition (PTSD, depression, or anxiety). The average self-rated health was 2.9 on a scale of 1 (poor health) to 5 (excellent health). Gender, age range, race, and deployment status were comparable with New Jersey VA veteran demographics.26

Table 1 shows veteran experience and interest in CAM practices. More than half of veterans who returned the survey reported doing either a CAM practice or having done 1 (n = 82; 61%). Many also reported interest in trying at least 1 practice (n = 73; 55%) or learning more about at least 1 practice (n = 71; 53%) either on their own or with an instructor. More veterans indicated they would prefer to try the techniques with an instructor (n = 61; 46%) rather than on their own (n = 26; 19%). Chi-square testing showed that interest and experience with CAM were not significantly associated with specific demographic characteristics.

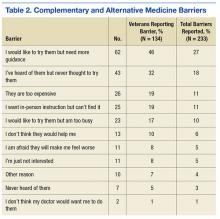

Several barriers to CAM practice were frequently cited (Table 2). The 2 most commonly endorsed barriers were veterans who wanted to try the techniques but needed more guidance (n = 62; 46%) and heard of CAM but never thought to try them (n = 43; 32%). Only a small percentage of veterans indicated that they did not think the practice would help (n = 13; 10%) or were concerned that it might hurt them (n = 11; 8%).

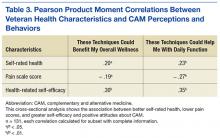

There were several significant bivariate associations (Table 3), although overall r2 values were low. More severe pain was associated with a weaker belief that the techniques could benefit overall wellness (r2 = – .19; P = .04) and help daily functioning (r2= – .27; P < .01). Higher health-related self-efficacy was associated with a stronger belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for overall wellness (r2= .30; P < .01) and daily function (r2 = .35; P < .01). Higher self-rated health was associated with stronger belief in effectiveness for overall wellness (r2 = .20; P = .02) and daily function (r2= .23; P < .01). One-way ANOVAs found no significant associations between belief in the techniques’ effectiveness for wellness or for daily activities (for which statistics are presented here) and positive screens for PTSD (F1,116 = 3.04; P = .08), depression (F1,116 = 2.06; P = .15), anxiety (F1,122 = 1.41; P = .23), or any of the 3 combined (F1,116 = 3.74; P = .06). None of the health factors was associated with veteran interest in trying a technique or with a history of trying at least 1 technique.

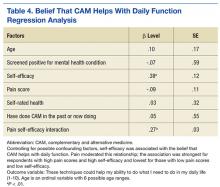

Of the multivariate linear regression models examining associations between veteran characteristics and responses to CAM, only 1 was significant (Table 4). Of all the factors in the model, only self-efficacy was significantly associated with the belief that CAM can improve daily function. Pain moderated this relationship; those with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with daily function only if they also had high self-efficacy (interaction term β = 0.27; SE = 0.03). For example, veterans with no pain (pain score 1 on a scale of 1-10) had a β = .07 (SE .13, P = .28), whereas those with the highest pain level (10) had a β = .92 (SE = .24, P = .001).

Discussion

The authors report 3 main findings from this study: Personal characteristics are not associated with experience, interest in, or belief in the efficacy of CAM; despite a large proportion reporting experience with CAM, veterans reported several barriers to using CAM; and the level of pain reported moderated the relationship between health-related self-efficacy and the belief that CAM will help with daily function.

Determining which personal characteristics are associated with CAM perceptions may indicate who is willing to try CAM techniques and who may require additional education or support. Although the authors hypothesized a difference in experience, interest, and belief of efficacy according to patient characteristics, these differences were not demonstrated. Some published research supports an association between white race, female sex, and middle or younger age and use of CAM, but this sample of veterans did not confirm these associations.1,3,6-8

The lack of associations may be related to selection bias, reflected in the relatively high report of baseline use of CAM. Nevertheless, this finding implies that clinicians should not make assumptions about an individual’s experience with CAM or interest in trying a modality. From a policy perspective, the VHA should consider a broad-based approach targeting a general audience or multiple segmented audiences to increase awareness and a trial of CAM for veterans.

Barriers should be considered when introducing CAM into routine clinical care. The current study revealed several important barriers to veterans accessing or trying CAM techniques, including need for guidance, the lack of awareness or access, and cost. The VHA services are often provided at low or no cost to eligible veterans, likely mitigating the cost barrier to a great extent. However, being able to easily access instruction in CAM modalities in a timely manner may be just as important. The authors detected a preference among respondents for classes to learn CAM (46%) vs independently (19%), supported by the commonly endorsed barrier to trying CAM of “I want in-person instruction but can’t find it.” Offering CAM modalities that can be taught in a group or individual setting and later practiced independently may be an appropriate approach to introduce CAM techniques to the largest number of people and encourage uptake. This approach can maximize access while satisfying many veterans’ preferences for in-person instruction. This leverage of skilled practitioner time could be extended for some modalities through remote telehealth participation or on-demand instruction, such as online videos or DVDs, including the SWK.

Chronic pain can be a challenge for patients and clinicians to manage, so the role of CAM in pain management is growing.2,27 The study’s findings suggest that motivating veterans with chronic pain to try CAM may take extra effort by the clinician. Multivariate linear regression modeling showed that respondents with higher pain levels believed CAM could help with their function only if they also had high health-related self-efficacy, whereas those with low pain scores reported this belief even with low self-efficacy. Thus, strong self-efficacy may overpower doubts about CAM that accompany having pain. Conversely, high reported pain levels may reduce self-efficacy and lead to doubts about the benefit of CAM.

In one study, the belief that lifestyle contributes to illness predicted CAM use, which is similar to this study’s finding that health-related self-efficacy predicted CAM use.8 Several other studies examined CAM use and self-efficacy, although usually not self-efficacy for general health management. To promote experimentation with CAM, patients with chronic pain may require interventions targeted to increase self-efficacy related to CAM.

Of the 733 surveys distributed to veterans, 134 (18%) responses were received. More than 60% of the respondents had tried a CAM technique, higher rates than reported by most other CAM utilization studies: U.S. prevalence studies range from 29% to 42% of respondents having tried some CAM technique, and studies of veterans or military personnel range from 37% to 50% having tried CAM.3,5-7 Because these studies asked about CAM generally or about specific practices that do not fully overlap with the independent CAM practices evaluated in the current study, it is difficult to assess how the experiences of the current sample compare with those populations.

Another study asked veterans with multiple sclerosis whether they were interested in trying CAM practices, and 40% responded “yes,” which is similar to 55% in the current study.6 It is possible the rate of experience with CAM is higher in the current study due to self-selection of respondents who were interested in the SWK. Another factor may be that some veterans were recruited from VA mental health clinics where independent CAM practices are more frequently offered.9 It is also possible that there are regional differences in CAM use; this study took place at a single facility in the northeast U.S., although subsequent phases of the SWK project involved more widespread national dissemination, to be reported in the future.