Few researchers have reported on the use of hormonal therapy for PPD. Yet significant hormonal fluctuations,56,57 including “estrogen withdrawal at parturition,”56 are known to occur after childbirth; in their study of women with severe PPD, Ahokas et al57 found that two-thirds of participants had serum estradiol concentrations below the cutoff for gonadal failure. Such a deficiency is likely to contribute to mood disturbances.56,57

In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that enrolled women with severe, persistent PPD (mean EPDS score, 21.8), six months’ treatment with transdermally administered estradiol was associated with significantly greater relief of depressive symptoms than was found in controls (mean EPDS scores at one month, 13.3 vs 16.5, respectively). Of note, more than half of the women studied were concurrently receiving antidepressants.58

Additional studies may elucidate the role of estrogen therapy in the treatment of PPD.

Nonpharmacologic Options

An effective nonpharmacologic option for rapid resolution of severe symptoms of PPD is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).59-61 Its use is safe in nursing mothers because it does not affect breast milk. ECT is considered especially useful for women who have not responded to pharmacotherapy, those experiencing severe psychotic depression, and those who are considered at high risk for suicide or infanticide.

Patients typically receive three treatments per week; three to six treatments often produce an effective response.59 Anesthesia administered to women who undergo ECT has not been shown to have a negative effect on infants who are being breastfed.60,61

Interpersonal strategies to address PPD should not be overlooked. A pilot study conducted in Canada showed promising results when women who had previously experienced PPD were trained to provide peer support by telephone to mothers who were deemed at high risk for PPD (ie, those with EPDS scores > 12). At four weeks and eight weeks postpartum, follow-up EPDS scores exceeded 12 in 10% and 15%, respectively, of women receiving peer support, compared with 41% and 52%, respectively, of controls.62

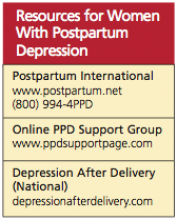

Participation in one of numerous support groups that exist for women with PPD (see box, for online information) may reduce isolation in these women and possibly offer additional benefits.

COMPLICATIONS

PPD may be associated with significant complications, underscoring the importance of prompt identification and treatment.5 Maternal depressive symptoms in the critical postnatal period, for example, have been associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. In one study of 101 women, lower-quality maternal bonding was found in women who had symptoms of depression at two weeks, six weeks, and four months postpartum—but not in those with depression at 14 months.63 Additionally, it was found in a systematic review of 49 studies that women with PPD were likely to discontinue breastfeeding earlier than women not affected.64

Delayed growth and development has been reported in infants of mothers with untreated or inadequately treated PPD.65 It has also been suggested that children of depressed mothers may have an increased risk for anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and other behavioral disorders later in childhood.65-67

PROGNOSIS

Untreated PPD may resolve spontaneously within three to six months, but in about one-quarter of PPD patients, depressive symptoms persist one year after delivery.24,68,69 PPD increases a woman’s risk for future episodes of major depression.2,5

PREVENTION

As previously discussed, the risk for PPD is greatest in women with a history of mood disorders (25%) and PPD (50%).2 Although several approaches have been studied to prevent PPD, no clear optimal strategy has been revealed. In one Cochrane review, insufficient evidence was found to justify prophylactic use of antidepressants.70 Similarly, findings in a second review fell short of confirming the effectiveness of prenatal psychosocial or psychological interventions to prevent antenatal depression.71

Additional studies are needed to make recommendations on prevention of PPD in high-risk patients. Until such recommendations emerge, close monitoring, screening, and follow-up are essential for these women.

CONCLUSION

Postpartum depression is an important concern among childbearing women, as it is associated with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. A personal history of depression is a major risk factor for PPD. It is imperative to question women about signs and symptoms of depression during the immediate postpartum period; it is particularly important to inquire about thoughts of harm to self or to the infant.

Pharmacotherapy combined with adjunctive psychological therapy is indicated for new mothers with significant depressive symptoms. The choice of antidepressants is based on previous response to antidepressants and the woman’s breastfeeding status. Generally, SSRIs are effective and well tolerated for major depression; based on results from small studies, they appear to be safe for breastfeeding mothers.

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a safe and effective option for women with severe symptoms of PPD.