THE WORKUP STARTS WITH A SEARCH FOR RED FLAGS

Evaluation of a patient with dyspepsia begins with a thorough history. Start by determining whether the patient has any red flags, or alarm features, that may be associated with a more serious condition—particularly an underlying malignancy. One or more of the following is an indication for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)5,8,12

• Family and/or personal history of upper GI cancer

• Unintended weight loss

• GI bleeding

• Progressive dysphagia

• Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

• Persistent vomiting

• Palpable mass or lymphadenopathy

• Jaundice.

While it is important to rule out these red flags, they are poor predictors of malignancy.23,24 With the exception of a single study, their positive predictive value was a mere 1%.8 Their usefulness lies in their ability to exclude malignancy, however; when none of these features is present, the negative predictive value for malignancy is > 97%.8

Age is also a risk factor. In addition to red flags, EGD is recommended by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) for patients with new-onset dyspepsia who are 55 or older—an age at which upper GI malignancy becomes more common. A repeat EGD is rarely indicated, unless Barrett esophagus or severe erosive esophagitis is found on the initial EGD.25

Physical exam, H pylori evaluation follow

A physical examination of all patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia is crucial. While the exam is usually normal, it may reveal epigastric tenderness on abdominal palpation. Rebound tenderness, guarding, or evidence of other abnormalities should raise the prospect of alternative diagnoses. GERD, for example, has many symptoms in common with dyspepsia but is a more likely diagnosis in a patient who has retrosternal burning discomfort and regurgitation and reports that symptoms worsen at night and when lying down.

Lab work has limited value. Although laboratory work is not specifically addressed in the AGA guidelines (except for H pylori testing), a complete blood count is a reasonable part of an initial evaluation of dyspepsia to check for anemia. Other routine blood work is not needed, but further lab testing may be warranted based on the history, exam, and differential diagnosis.

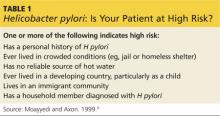

H pylori risk. Because of the association between dyspepsia and H pylori, evaluating the patient’s risk for infection with this bacterium, based primarily on his or her current and previous living conditions (see Table 1),9 is the next step. Although a test for H pylori could be included in the initial work-up of all patients with dyspepsia, a better—and more cost-effective—strategy is to initially test only those at high risk. (Testing and treating H pylori will be explored further.)

INITIATE ACID SUPPRESSION THERAPY FOR LOW-RISK PATIENTS

Firstline treatment for patients with dyspepsia who have no red flags for malignancy or other serious conditions, and either are not at high risk for H pylori or are at high risk but have tested negative, is a four- to eight-week course of acid suppression therapy. Patients at low risk for H pylori should be tested for the bacterium only if therapy fails to alleviate their symptoms.9

H2RAs or PPIs? A look at the evidence

In a Cochrane review, both H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were significantly more effective than placebo for treating FD.26 However, H2RAs can lead to tachyphylaxis—an acute decrease in response to a drug—within two to six weeks, thus limiting their long-term efficacy.27

PPIs appear to be more effective than H2RAs and are the AGA’s acid suppression drug of choice.11 The CADET study, a randomized controlled trial comparing PPIs (omeprazole 20 mg/d) with an H2RA (ranitidine 150 mg bid) and a prokinetic agent (cisapride 20 mg bid) as well as placebo for dyspepsia, found the PPI to be superior to the H2RA at six months.28 In a systematic review, the number needed to treat with PPI therapy for improvement of dyspepsia symptoms was 9.29

There is no specified time limit for the use of PPIs. AGA guidelines recommend that patients who respond to initial therapy stop treatment after four to eight weeks.11 If symptoms recur, another course of the same treatment is justified; if necessary, therapy can continue long term. However, patients should be made aware of the risk for vitamin deficiency, osteoporosis, and fracture, as well as arrhythmias, Clostridium difficile infection, and rebound upon abrupt discontinuation of PPIs.

Continue for when to test for H pylori ... >>