BASAL PLUS ONE STRATEGY

To best utilize prandial insulin, it is important to know what the patient’s glucose readings are before and after meals as assessed by the 7-point or staggered blood glucose monitoring techniques described earlier. Once you have clarified which meal(s) are raising the patient’s glucose levels, selecting appropriate treatment becomes easier. To reduce the glucose-monitoring burden for the patient, it may be acceptable to allow the patient to omit the fasting glucose measurement (if stable).

The first major decision is whether to treat one meal per day (basal plus one) or all meals (basal-bolus). Adding a rapid-acting insulin prior to one meal a day (usually the largest meal) is a reasonable starting point.16

The meal that produces the highest postprandial glucose readings can be considered the meal of greatest glycemic impact. The delta value—the difference between pre-meal glucose and 2-hour postprandial glucose readings—also helps to determine the largest meal of the day.17 The average physiologic delta is ≤ 50 mg/dL.17 If the delta for a meal is > 75 mg/dL, consider initiating prandial insulin prior to that meal and titrating the dose to achieve a target glucose level of < 130 mg/dL before the next meal.

Using 4 to 6 units of a rapid-acting insulin per meal is a good initial regimen for a basal plus one (as well as for a basal-bolus) approach.16 If the patient experiences significantly increased insulin demands as indicated by glucose patterns where the postmeal glucose is still consistently above 180 mg/dL, the initial regimen may be modified to 0.1 U/kg per meal,17-19 and then titrated up to a maximum of 50% of the total daily insulin dose (TDD) for basal plus one (or 10%-20% of TDD per meal for basal-bolus).16

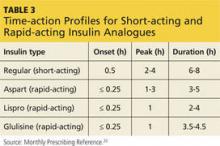

Consider the timing of administration. Rapid-acting insulin analogues exhibit peak pharmacodynamic activity 60 minutes after injection (see Table 3).20

Peak carbohydrate absorption following a meal occurs approximately 75 to 90 minutes after eating begins.17,21 Thus, to synchronize the action of insulin with carbohydrate digestion, the analogue should be injected 15 minutes before meals. This can be increased by titrating prandial insulin by 1 U/d to a goal of either a 90-minute to 2-hour postprandial glucose of < 140 to 180 mg/dL or the next preprandial glucose of < 130 mg/dL.16 The goal is to obtain a near-normal physiologic delta of < 50 mg/dL. The drop in delta noted with every unit of insulin added to the current dose can provide a rough approximation of how many additional insulin titrations will be needed to achieve a delta of < 50 mg/dL.

BASAL-BOLUS COMBINATION

A gradual increase from one injection before a single meal each day to as-needed multiple daily injections (MDIs) is the next step in hyperglycemia management. Starting slow and building up to insulin therapy prior to each meal offers structure, simplicity, and clinician-patient confidence in diabetes management. The slow progression from basal plus one to basal-bolus combination allows the patient to ease into a complex, labor-intensive regimen of MDIs. Additionally, the stepwise reduction of postprandial hyperglycemia with this slow approach often reduces the incidence of hypoglycemia (more on this in a moment).8

Advanced insulin users can calculate an “insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio” (ICR) to estimate the amount of insulin they need to accommodate the amount of carbohydrates they ingest per meal. An ICR of 1:10 implies that the patient administers 1 unit of insulin for every 10 grams of carbohydrates ingested. For example, if a patient with an ICR of 1:10 concludes that his meal contains a total of 60 grams of carbohydrates, then he would administer 6 units of insulin prior to this meal to address the anticipated post-meal hyperglycemia.

In order to use the ICR regimen, a patient would need to be able to accurately determine the nutritional content of his meals (starch, protein, carbohydrates, and fat) and calculate the appropriate insulin dosage. For successful diabetes management, it is essential to evaluate the patient’s skills in these areas before starting an ICR regimen and to routinely assess hypoglycemic episodes at follow-up visits.

An ICR approach is usually reserved for patients who require tighter glucose control than that obtained from fixed prandial insulin doses, such as patients with type 1 diabetes, those with variable meal schedules and content, those with a malabsorption syndrome that requires consuming meals with a specific amount of carbohydrates, athletes on a structured diet with specific carbohydrate content, and patients who want flexibility with carbohydrate intake with meals.

The risk for hypoglycemia is a major barrier to initiating basal-bolus insulin therapy. Hypoglycemia is classified as a blood glucose level of < 70 mg/dL, and severe hypoglycemia as < 50 mg/dL, regardless of whether the patient develops symptoms.22 Symptoms of hypoglycemia include dizziness, difficulty speaking, anxiety, confusion, and lethargy. Hypoglycemia can result in loss of consciousness or even death.22

A patient who has frequent hypoglycemic episodes may lose the protective physiologic response and may not recognize that he is experiencing a hypoglycemic episode (“hypoglycemia unawareness”). This is why it is crucial to ask patients if they have had symptoms of hypoglycemia and to correlate the timing of these symptoms with blood glucose logs. For example, it is possible for a patient to experience hypoglycemic symptoms for blood glucose readings in the 100 to 200 mg/dL range if his or her average blood glucose has been in the 250 to 300 mg/dL range. Such a patient may not realize he is experiencing hypoglycemia until he develops severe symptoms, such as loss of consciousness.

Hypoglycemia unawareness must be addressed immediately by reducing insulin dosing to prevent all hypoglycemic episodes for two to three weeks. This has been shown to “reset” the normal physiologic response to hypoglycemia, regardless of how long the patient has had diabetes.23,24 Even if your patient is aware of the warning signs of a hypoglycemic episode, it is important to routinely ask about hypoglycemia at all diabetes visits because patients may reduce insulin doses, skip doses, or eat defensively to prevent hypoglycemia.

Other than the risk for hypoglycemia, insulin typically has fewer adverse effects than oral medications used to treat diabetes. Most common concerns include weight gain, injection site reactions and, rarely, allergy to insulin or its vehicle.16

REFERENCES

1. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. AACE Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:327-336.

2. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient centered approach. A position statement of the ADA and the EASD. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364-1379.

3. Shubrook J. Insulin for type 2 diabetes: How and when to get started. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:76-81.

4. Nathan D, Buse J, Davidson M, et al; American Diabetes Association; European Association for Study of Diabetes. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193-203.

5. Rosenstock J, Fonseca VA, Gross JL, et al. Advancing basal insulin replacement in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with insulin glargine plus oral agents: a comparison of adding albiglutide, a weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist, versus thrice daily prandial insulin lispro. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2317-2325.

6. Owens DR, Luzio SD, Sert-Langeron C, et al. Effects of initiation and titration of a single pre-prandial dose of insulin glulisine while continuing titrated insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes: a 6-month ‘proof-of-concept’ study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:1020-1027.

7. Lankisch MR, Ferlinz KC, Leahy JL, et al; Orals Plus Apidra and LANTUS (OPAL) study group. Introducing a simplified approach to insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a comparison of two single-dose regimens of insulin glulisine plus insulin glargine and oral antidiabetic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:1178-1185.

8. Davidson MB, Raskin P, Tanenberg RJ, et al. A stepwise approach to insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and basal insulin treatment failure. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:395-403.

9. Owens DR. Stepwise intensification of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes

management—exploring the concept of basal-plus approach in clinical practice. Diabet Med. 2013;30:276-288.

10. Holst J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1409-1439.

11. Byetta [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

12. Bydureon [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

13. Victoza [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2015.

14. Tanzeum [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

15. Trulicity [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2014.

16. Vaidya A, McMahon GT. Initiating insulin for type 2 diabetes: Strategies for success. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2009;16:127-136.

17. Unger J. Insulin initiation and intensification in patients with T2DM for the primary care physician. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:253-261.

18. Sharma MD, Garber AJ. Progression from basal to pre-mixed or rapid-acting insulin—options for intensification and the use of pumps. US Endocrinology. 2009;5:40-44.

19. Mooradian AD, Bernbaum M, Albert SG. Narrative review: A rational approach to starting insulin therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:125-134.

20. Monthly Prescribing Reference (MPR). Insulin. www.empr.com/insulins/article/123739/. Accessed June 19, 2015.

21. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Insulin, glucagon, and diabetes mellitus. In: Guyton AC, Hall JE, eds. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2006:961-977.

22. Kitabchi AE, Gosmanov AR. Safety of rapid-acting insulin analogs versus regular human insulin. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344:136-141.

23. Cryer PE. Diverse causes of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2272-2279.

24. Gehlaut RR, Shubrook JH. Revisiting hypoglycemia in diabetes. Osteopathic Fam Phys. 2014;1:19-25.